Alternatively, if the claim relates to

a category that is excluded from

patentability but “clearly does not seek

to tie [it] up” a streamlined analysis can

be used in step 2a. An example of such

a claim provided by the USPTO refers

to an artificial hip prosthesis coated

with a naturally occurring mineral. This

use of the naturally occurring product

does not claim the naturally occurring

mineral per se, just its use with the

prosthesis and is therefore held to

represent subject matter that is not

excluded from patentability.

However, assuming the analysis

at step 2a comes out as “yes”, the

analysis must proceed to step 2b.

In step 2b the test is whether any

part or combination of parts of the

claim amounts to “significantly more”

than the exception itself. This means

that “the claim describes a product

or process in a meaningful way,

such that it is more than a drafting

effort designed to monopolise the

exception”. Unfortunately, all of the

examples provided to date as to

what might be “significantly more”

relate to mechanical or electronic

fields of technology (although the July

2015 update promises that further

biodiagnostic related examples will

be forthcoming). The USPTO does

note that the steps of “administering”

(e.g. a compound) or “determining”

(e.g. a concentration of analyte)

are not sufficient to satisfy the

requirements of “significantly more”.

Biodiagnostic cases are struggling in

the wake of this new approach. So,

what can applicants in this field do?

The analysis provided in the USPTO

interim guidance appears to be

especially concerned with preventing

applicants from trying to monopolise

subject matter, such as natural

laws, that is excluded from patent

protection. One option for applicants

in the biodiagnostics field may be

to argue that the claims relate to

practical applications of a natural law

and do not seek a monopoly in the

natural law per se. For this to work

it is likely that the claims will need

to include active steps, especially

definite steps of treatment or

making a diagnosis (which will need

to amount to more than “thinking

about the results”). Sensible fall back

positions may include specifying

the methods by which those

treatment or diagnostic steps are

carried out, e.g. specifying the use

of specific antibodies or a particular

type of assay. Of course, this may

lead to narrower claims and these

limitations will need to be drafted

carefully.

As personalised medicine becomes

increasingly important, biodiagnostic

and biomarker testing is becoming

critical for effective diagnosis and

treatment of patients. Unfortunately,

due to the significant cost required

to establish the safety and efficacy

of products before they can reach

the market, companies simply

cannot afford to develop these

products without patent protection.

Consequently, there is a real risk that

these developments in US case law

could lead to fewer new products

reaching patients. For this reason,

a European approach, which leaves

doctors and medical practitioners

free to treat or diagnose their

patients as they see fit, while

protecting the products associated

with those methods, seems to be

significantly preferable. Recently the

USPTO’s stance has been challenged

by amicus curiae briefs from

interested groups around the world,

so perhaps in time common sense

will prevail.

13

To find out more

contact Helen Henderson

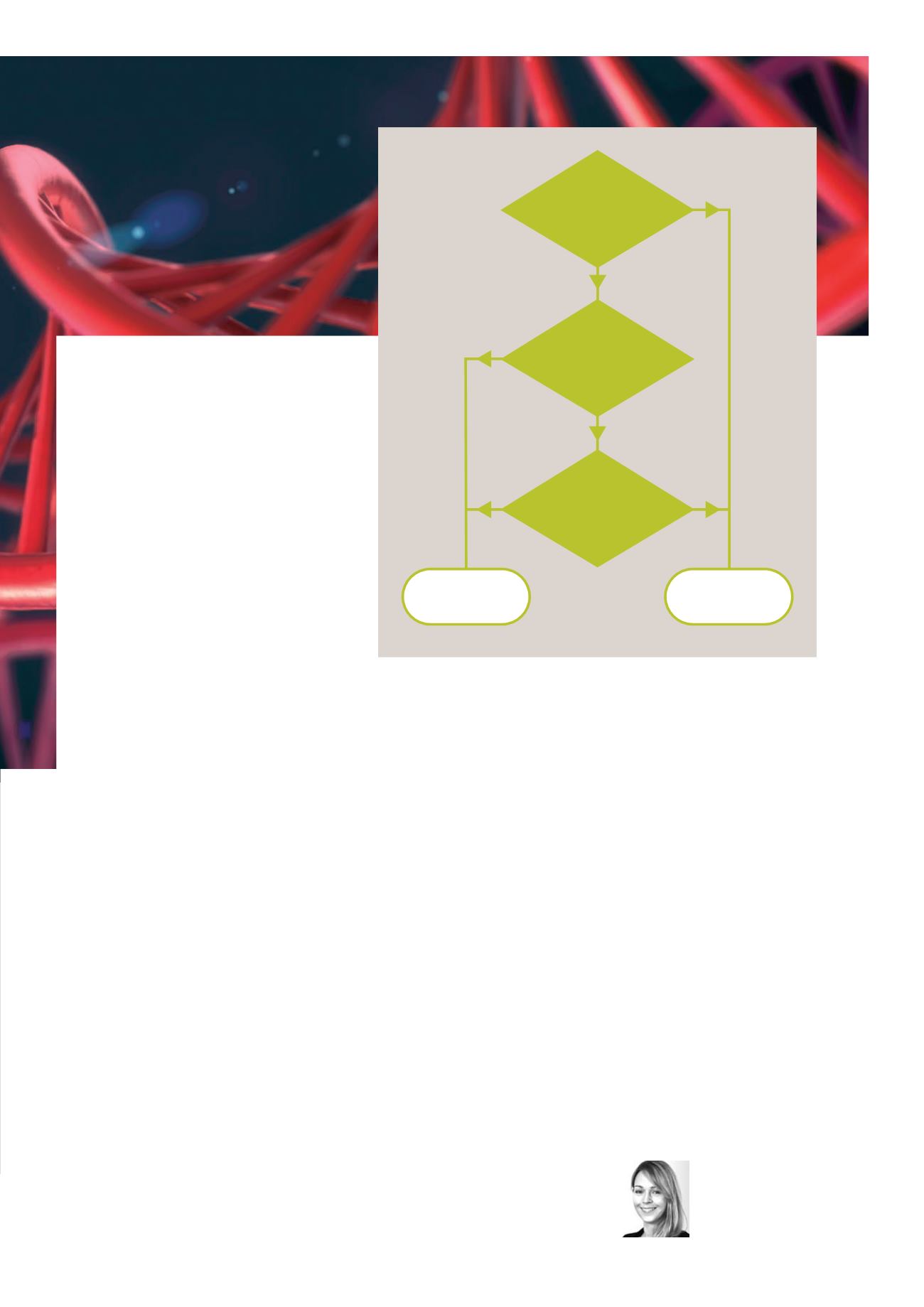

Step 1

IS THE CLAIM TO A PROCESS,

MACHINE OR COMPOSITION OF

MATTER?

Step 2a

IS THE CLAIM DIRECTED TO

A LAW OF NATURE, A NATURAL

PHENOMENON OR AN ABSTRACT

IDEA (JUDICIALLY RECOGNIZED

EXCEPTIONS)?

Step 2b

DOES THE CLAIM RECITE

ADDITIONAL ELEMENTS THAT

AMOUNT TO SIGNIFICANTLY MORE

THAN THE JUDICIAL

EXCEPTION?

CLAIM QUALIFIES AS

ELIGABLE SUBJECT MATTER

UNDER 35 USC 101

CLAIM IS NOT ELIGABLE

SUBJECT MATTER UNDER

35 USC 101

NO

NO

NO

YES

YES

YES