News

Patentability of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Inventions in Europe

22 March 2018

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is an interdisciplinary field of computer science with the goal of enabling machines to behave and reason in an intelligent manner. Early approaches to AI centred on rule-based systems. Such systems were configured to operate within highly constrained environments where the behaviour of the AI system was specified beforehand using formal rules. Knowledge was represented as a set of rules from which the AI system could determine outcomes to given problems. Expert systems were a popular example of rule based AI. Knowledge was typically represented as a structure of if-else rules that could be traversed in order to find a solution to a given problem or question. Applications of expert systems included real time process control, medical diagnosis, and safety critical systems. However, such rule based systems were typically unable to generalise[1] and reason beyond the knowledge provided.

Machine learning is a subset of AI that seeks to move away from rule-based approaches and move towards approaches that can generalise. Machine learning algorithms are typically characterised by their learning from data. Specifically, machine learning algorithms aim to use the data to learn a mapping function from the input data space to an output data space. Input data consists of a number of instances, each of which has a number of features. In supervised machine learning, each input instance has a corresponding output instance and the algorithm is said to be trained on this data, often referred to as the training data. That is, for a given function that maps from the input space to the output space, the training data is used to find a set of parameters for the function that produces the lowest error (i.e. the outputs predicted by the function for the set of inputs, closely match the inputs’ actual outputs). This learnt function can then be used to make predictions on previously unseen data. As such, machine learning aims to generalise to unseen data in a way that classical AI algorithms cannot.

One of the most powerful approaches to machine learning has proven, at least in part, to be founded upon biological principles – the Artificial Neural Network (ANN), or simply Neural Network (NN). A neural network is a connectionist approach that takes inspiration from the way that the brain’s neurons are wired and interact. An artificial neural network consists of a number of nodes (neurons) connected by edges. Each edge has a corresponding weight, and each node has an activation function that operates upon the incoming edges of the node. Nodes are typically grouped together into layers, with the outputs of a preceding layer feeding into the inputs of the next layer. During training, the edge weights are iteratively updated so that the output of the network for a given input closely matches the input’s actual output.

Arguably the most important development in machine learning in recent years is that of deep learning. Deep learning builds upon traditional artificial neural networks by deploying them at scale. That is, thanks to the increase in relatively cheap computing power, neural networks containing billions of weights can be trained on massive amounts of data. Unlike traditional machine learning algorithms, where the features of the input data are often carefully crafted prior to training, deep learning aims to learn a set of features from the data. That is, deep learning not only aims to learn the mapping from the input space to the output space, but also seeks to learn the features that best provide this mapping. The wide adoption of deep learning to a range of complex problem domains, from speech recognition to medical image diagnosis, demonstrates the power and effectiveness of these algorithms.

Patentability of AI and Machine Learning Inventions

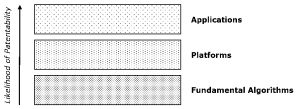

When considering the patentability of AI and machine learning inventions, it is useful to coarsely group such inventions into three categories: fundamental algorithms, platforms, and applications.

graph showing likelihood of patentability for applications, platforms and fundamental algorithms

Inventions within the fundamental algorithms category are related to the AI and machine learning algorithms themselves, without any consideration of application to a specific problem. Applications falling within this category are the least likely to be granted patent protection within Europe. Therefore, machine learning algorithms per se cannot be patented within the European system as they would be deemed a mathematical method, and mathematical methods as such are deemed to be non-inventions (Article 52(2)(3) EPC).

Inventions considered to be within the platform category are those that go a step beyond the mere algorithms themselves and attempt to provide a platform from which a problem can be solved, without explicitly restricting the scope of the invention to a specific application area. EP2948877B1 is one such example of a granted platform patent. The invention relates to a method for image retrieval based on image segmentation and feature descriptors. However, the invention is not disclosed as being related to a specific application area such as medical image retrieval. A further example of a platform patent is EP1770612B1, which discloses a method for distributed training of a Support Vector Machine (SVM). The technical character of the disclosed invention is obtained from the fact that the SVM is trained across multiple distributed local sets. As such, the application is not a fundamental algorithm per se.

Inventions that are within the applications category are those that seek to apply machine learning or artificial intelligence to solve a specific problem, often without restricting the solution to a specific algorithm. These applications are considered the most likely to be deemed patentable by the European Patent Office. A recent example of an application patent is EP2377044B1, which uses a machine learning algorithm to detect anomalous patterns in video data over long time periods. A further example is given by EP2930578B1, which discloses a method for classifying the cause of machine failure by using machine learning to analyse features obtained from sensors. Inventions within this category are typically characterised by the fact that they are focussed more on the application area, e.g. machine failure, than the machine learning or artificial intelligence algorithms used.

Therefore, despite the numerous approaches to AI, and the obvious difference between AI based software systems and traditional software systems, the approach to patenting such systems remains largely the same. As with any computer related invention, AI and machine learning inventions will need to produce a relevant technical effect, or provide a technical solution to a technical problem. When considering a patent application related to AI or machine learning, it is beneficial to bear in mind which of the three categories the patent is most closely related to. In so doing, it may be possible to provide a clearer focus to the application which in turn may help to demonstrate the technical character of the invention.

Relevant case law

The relevant case law of the Technical Boards of Appeal of the EPO support the above opinions regarding the patentability of AI and machine learning inventions.

In T1784/06, the invention related to a means of classifying a set of data records. The board held that the problem was non-technical since the automatic classification of data records serves only the purpose of classifying the data records, without implying any technical use of the classification. Further, the board did not consider the enhanced speed of the algorithm, when compared to other algorithms, as being sufficient to establish a technical character of the algorithm (c.f. T1227/05, point 3.2.5).

T0297/86 concerns the automatic control of a printing press, which is characterised by the use of linear regression analysis to correlate subjective and objective harmonic analysis data related to print quality and obtain regression parameters. These parameters, once learnt, can then be used to predict the subjective data based on objective data obtained. The board held that the use of linear regression and harmonic analysis data was indeed inventive when applied to the specific problem.

In T1358/09, the board stated that the task of document classification based on their textual content was non-technical. As in T1316/09, the board held that methods of text classification per se did not produce a relevant technical effect or provide a technical solution to any technical problem.

Even when a technical means to a technical problem is given, it is important to distinguish the novel features from the prior art. In T1148/05, the application related to a method for classifying images according to low-level features used within a decision tree algorithm. The board held there to be a technical effect, but the low-level features described by the applicant were known in the prior art. As such, the application of these features to the problem was deemed to be obvious.

Ownership[2]

Under current patent law, the named inventors of a patent application must be an ‘individual’ or ‘person’, as opposed to a corporate entity. To qualify as an ‘inventor’, an individual must have actually devised part of the inventive concept. Merely applying a machine learning or AI algorithm to a specific problem should not be construed as the algorithm contributing a part of the inventive concept. However, if the machine learning or AI algorithm has contributed a part of the inventive concept, as in The Creative Machine[3], then there is currently a lack of clarity regarding the ownership of artificially-generated inventions.

At present, it appears that for the case of machine learning or AI being applied to a specific problem, the issue of ownership remains the same as for any other patent application. However, if the machine learning or AI algorithm has contributed to the inventive concept with which the patent application is concerned, then current patent law remains unclear as to who owns the invention in this instance. The issue becomes even more murky in collaborative approaches to innovation (such as “open innovation”) where several parties might contribute to an innovation using different means for development including a distributed AI network. In such scenarios we envisage huge potential for dispute of contribution and inventorship of potentially very valuable innovation.

Conclusions

Due to its obvious commercial significance, an increase in the number of patent filings related to artificial intelligence and machine learning will likely be seen in the coming years. The European Patent Office is starting to anticipate such a scenario and is organising specific meetings related to the patentability issues of artificial intelligence inventions. At present, the patentability issues for AI and machine learning inventions remain largely the same as any other computer related invention. The fundamental algorithms per se remain excluded under European patent law, but applications of such algorithms to solve technical problems are deemed patentable. There still remains numerous unanswered questions related to patentability issues of AI and machine learning inventions, such as the ownership question. It will be telling whether answers to such questions will be provided by relevant case law over the coming years.

Dr Harry Strange and Dr Karl Barnfather

Electronics, Computing & Physics group

[1] Within this context, generalisation refers to the ability of an AI algorithm to respond meaningfully in situations it has hitherto not encountered.

[2] Section adapted from “Can computers and AI systems really be inventors?“ by Stuart Latham and Diego Black, Withers & Rogers LLP.

[3] IEI’s Patented Creativity Machine Paradigm.

If you require further information on anything covered in this briefing, please contact Harry Strange (hstrange@withersrogers.com; 44 20 7940 3600) or your usual contact at the firm. This publication is a general summary of the law. It should not replace legal advice tailored to your specific circumstances.

© Withers & Rogers LLP, March 2018