Biotech companies will want to obtain

Europe-wide protection via the EPO, but

then avoid litigation in the Netherlands,

Germany and France. On the other

hand, farmers and plant breeders may

look to exploit the national provisions of

these countries.

To find out more

contact Jon Elsworth

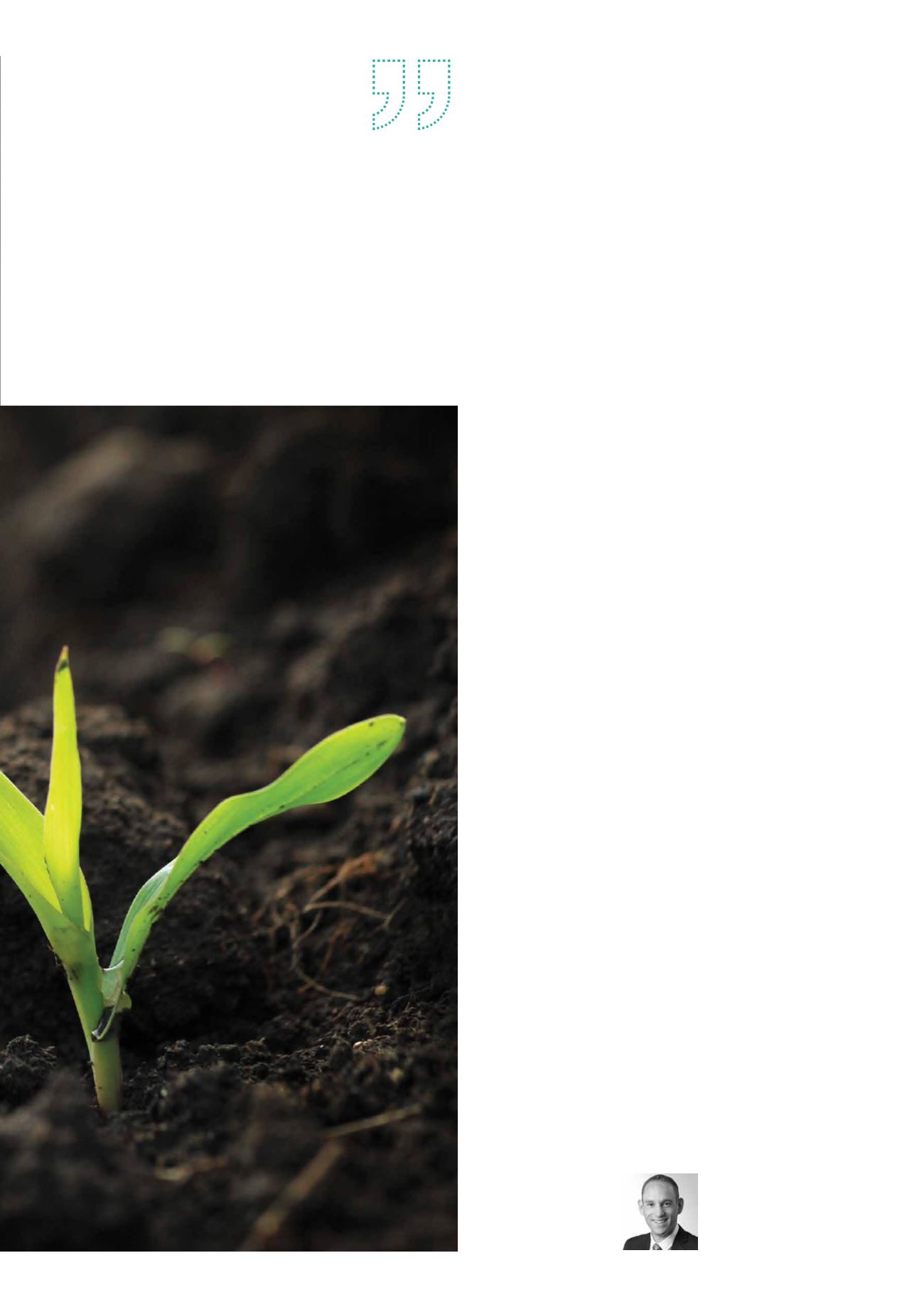

To avoid the exclusion, the technical step would have to

introduce or modify a genomic trait, with the result being

a genotype that goes beyond simple mixing of the chosen

parent plant genomes by conventional, sexual crossing.

The more recent “Tomato II” and “Broccoli II” cases, G2/12

and G2/13, looked more closely at how to treat products

which are themselves novel (new plant parts) but which

are defined (in a patent application) as having been

made by an essentially biological process. Ultimately,

the EBA held that the exclusion does not extend to the

products of essentially biological processes, thereby

allowing companies to develop and protect, via the EPO,

improvements in plant-derived products.

However, farmers and breeders’ associations expressed

concerns over the “Tomato II” and “Broccoli II” cases

as threatening biodiversity and limiting market fluidity,

rendering farmers more reliant on a small number of

international organisations who hold patent rights.

This is a view shared by Dutch and German legislators,

who, in 2010 and 2013 respectively, enacted provisions

in their national laws to prevent products obtained by

means of essentially biological processes from being the

subject of patent protection.

The French authorities are now likely to follow suit, after

indicating their determination to “remove obstacles

to innovation caused by the multiplication of patent

applications on life and the growing concentration of

the patent holders, at the expense of the plant varieties

certificates.” However, an amendment to the proposed

bill was generally supported, which aims to limit the scope

of the exclusion to only animal and plant products.

These differences in the national laws of the Netherlands,

Germany and France compared to the EPO will likely

have important implications on where European patents

covering products obtained by essentially biological

processes are enforced. Biotech companies will want

to obtain Europe-wide protection via the EPO, but then

avoid litigation in the Netherlands, Germany and France.

On the other hand, farmers and plant breeders may look

to exploit the national provisions of these countries.

A factor that will inevitably complicate matters further is

the arrival of the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent

Court. Biotech companies will no doubt follow with

interest developments at the Central Division of the UPC

that is charged with handling litigation of patents in this

field, and may look favourably on the Unitary Patent

system if the court appears inclined to follow the case law

of the EBA.

15